What Loophole Allows The Government To Use Private Savings To Fund Public Retirement Payments?

by Daniel R. Amerman, CFA

Over the coming decades, the United States government has extraordinarily expensive public retirement promises to pay for (as do many other nations).

The current official national debt of over $17 trillion already amounts to about $180,000 per above poverty line household. However, if we take into account the (present) value of future unfunded obligations, mostly consisting of promised medical and other retirement benefits, then as has been frequently reported, the true national debt is (depending on the source) somewhere between $60 trillion and $200 trillion. A reasonably well accepted figure is the $87 trillion estimate by Archer and Cox (former chairman of the House Ways and Means committee, and former SEC chairman.)

That means the government has to come up with an additional $70 trillion in the coming decades, over and above what is expected to be taken in with current tax rates and projected economic growth. Assuming that the government can only get this money from those who have an ability to pay – the above poverty line households – this means that the government needs to come up with an additional $720,000 per household.

Obviously, that won't work, at least not with dollars that are worth what they are today. And therefore, current retirement promises are unlikely to be paid in full. Meanwhile, tens of millions of workers have been paying payroll taxes for decades, in the belief that they are legally entitled to their Social Security and Medicare benefits in full.

This could lead to many angry voters. And naturally, the greater the shortfall between what was promised and what is actually paid out, the angrier these tens of millions of voters are likely to be. So politicians have an enormous incentive to come up with as much of that $720,000 per above poverty line household as they can, and they are likely to be quite resourceful in trying to find ways of doing so.

This has led many people to fear that at some point the government will "go where the money is", which is private savings and wealth, and most particularly, private retirement accounts. There are fears of forced investment of retirement assets into Treasury bonds that would be used to pay public retirement obligations. Or there could be a forced merger of private pension assets into a bankrupt public retirement system, much like Poland did with its "bail-in" of its retirement system in 2013.

However, such high drama and above board actions could lead to the same problem that politicians are trying to avoid – tens of millions of very angry voters. The government thus has a strong preference to acquire the money in a manner in which the voters don't understand what is going on.

Can this be done?

As explored in this analysis, it can, and already is being done. The government already has a subtle means of taking investor wealth on a massive scale – including from retirement accounts.

And because this demonstrably meets the government's dual needs of getting the money without enraging the voters, there is every reason to believe that as the government seeks the tens of trillions of dollars needed to even partially close the shortfall in funding public retirement promises, it will ratchet up this hidden taking of private investor wealth on an ever greater scale.

The "Secret Weapon" For Taking Investor Wealth

The government's "secret weapon" is that it controls both the value of money and the tax code. And by changing the value of money, the government can generate "phantom profits" that don't really exist at all – there is no economic benefit to investors. However, because the government's tax code treats "phantom profits" as entirely real, it can tax every investor in the country on these government-created changes in the value of money, and do so repeatedly, stripping away another layer of each investor's starting net worth with each year that goes by.

The decreases in the value of money which create "phantom profits" are of course also known as "inflation". From the government’s perspective, inflation offers the ability to transform after-tax investor assets into pre-tax income, which can then be taken from individuals through an effective “Inflation Tax.” With ongoing inflation, running the gauntlet of taxes once or twice is not enough, and even your after-tax net worth can be repeatedly raided under government tax policy by using the pretext of non-existent income – that was itself created by government monetary and fiscal policy.

This educational resource will precisely demonstrate the way this little-known wealth seizure strategy works, and the multiple levels of challenges it presents. It will do so in three parts:

1. A round number tutorial that illustrates how this hidden taking works, step by step.

2. A historical review that shows how over a 15 year period – even in a time of low reported inflation – the government was not only able to take 100% of real stock price gains from tens of millions of unknowing stock investors, but to also take part of their starting after-tax savings.

3. A look forward that demonstrates how raising the rate of inflation enables the government to take potentially trillions of dollars of private wealth from investors, from both inside and outside of their retirement accounts, in a manner that the general public never has understood – and likely never will.

There are ways that we can protect ourselves from this deeply unfair tax. Indeed, we can even reverse it, so that instead of paying real taxes on phantom income, we (quite legally) pay phantom taxes on real income. But to do so we first have to see this hidden wealth transfer mechanism, and to thoroughly understand it.

Seizing Assets Through Inflation Taxes

The easiest way to illustrate the Inflation Tax is with an example scenario. Let’s assume that through hard work and deferred gratification, you built up $40,000 in savings, which wasn’t easy after paying all the taxes on the income as you made it. Through judicious investing, you turned that $40,000 into a $100,000 current investment portfolio. Which again wasn’t helped by paying taxes on every dollar of gain, but you’ve made it, the $100,000 is yours after-tax, and the government has no tax claim on it.

So long as a dollar stays worth a dollar, that is.

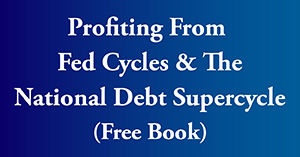

Chart I below illustrates how by changing the value of the dollar, part of your after-tax assets can be taken by the government. This could happen in a year or two, or it could happen over ten or twenty years.

The left column represents nominal dollars. You buy almost any kind of asset for $100,000, and hold it long enough and in most cases you will be eligible for long-term capital gains tax treatment. During that time, inflation destroys half the value of the dollar, meaning it now takes $2 to buy what $1 used to.

Our key assumption is that your asset exactly keeps up with the surge of inflation – meaning it likely did better than most investments. So you get $200,000 when you sell it – even though in purchasing power or real dollar terms, the asset is unchanged in value (the right column, and the dark green blocks and bars are real dollars).

The government does not generally recognize inflation in its tax policy, but rather sees only nominal dollars (the pale yellow bars and boxes). In other words, what the government sees is that you just made $100,000, and it wants its share in the form of $20,000 in capital gains taxes. Now as long as we ignore inflation, that’s not so bad. We still have $80,000 in “profits”. Indeed, that 80% after-tax return on investment may look pretty sweet.

The problem is when we adjust our 80% after-tax return for the technicality of a dollar only buying what fifty cents used to. That is, when we look at our real wealth in terms of the goods and services we can buy with the proceeds of selling our asset. When we go down the Real Dollars column and look with our dark green economic “eyes”, we see that we bought the asset for $100,000, and sold it for $100,000; therefore in terms of real wealth – our pre-tax gain is zero. But, we still have to pay taxes. When we discount those future taxes to bring them back to current dollars, at least it drops the real cost in half, down to $10,000. So once we pay those taxes – in purchasing power terms we have $90,000 left.

Meaning that instead of making an $80,000 profit, as it appeared when looking at our tax return – we in fact lost $10,000 out of our $100,000 investment in real terms. We see that when we adjust for inflation and look at what a dollar will buy – our sweet 80% return vanishes, and what we are left with is a 10% loss on our investment.

We just met the “Inflation Tax”. And it ran over us.

Let’s review what just happened here. Through its monetary and fiscal policies, the government created inflation that cut the value of our dollars in half. Meaning that in dollar terms, everything that we owned, such as bank accounts and bonds, just had half the value taken away. However, we were fortunate enough not to put our $100,000 into a dollar-denominated investment, but rather into another type of asset that kept up with inflation on a pre-tax basis. We didn’t actually make any real money, we just protected the purchasing power of our assets against the effects of unwise government policies.

So how does the government react? By stripping us of part of the wealth we did preserve, on the grounds of illusionary profits. With the illusion that created the pretext for seizing our assets having been created by the government in the first place.

Recent History & Using Low Rates Of Inflation To Take Stock Investor Wealth

If one fully accepts the principles explored in this article, the results can be both paradigm changing and even life changing. However, human nature being what is, paradigm change can be a quite uncomfortable process – and many people vigorously resist it. They would rather ignore what is happening, even if it means paying hidden taxes on a massive scale, instead of re-examining decades of personal beliefs about money, investments, governments and taxes.

So some might dismiss the scenario above, perhaps rationalizing that it is just a made-up example, with round numbers and an unrealistically high degree of inflation. With this dismissal being followed by trying to forget about this whole deeply disturbing perspective as soon as possible.

This dismissal wouldn't change the truth, however, because when we look at real history with real stock prices and official government reported low rates of inflation – inflation taxes are still there. And it is easy to show that the government is indeed taking massive amounts of wealth from tens of millions of unknowing victims in the real world.

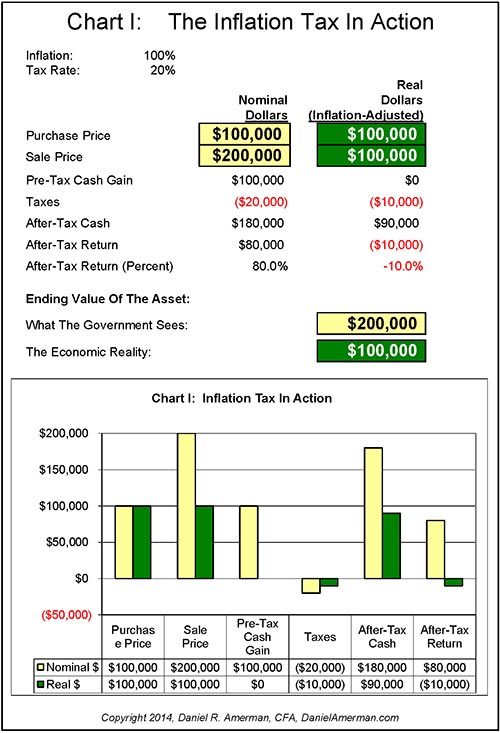

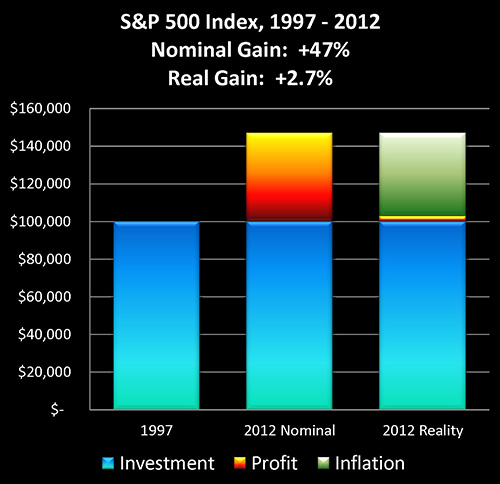

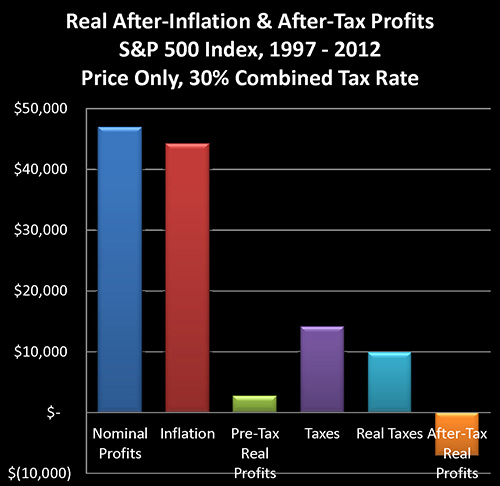

To explore one such real world example, let's take a look at the following graph and chart for the Standard & Poor's 500 between the end of 1997 and the end of 2012.

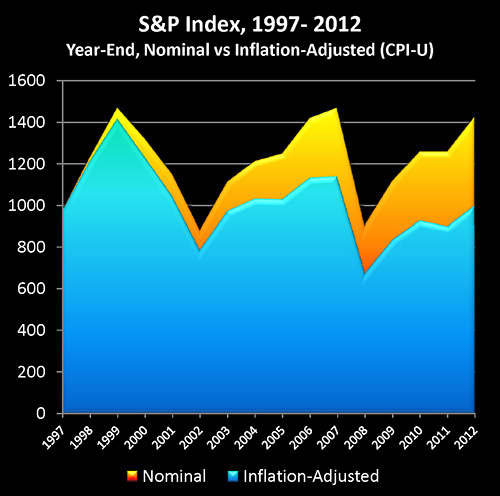

The Standard & Poor's 500 at the end of 1997 had a value of 970, and by the end of 2012 had reached a value of 1426 (as shown in yellow), which was in nominal terms a quite impressive gain of 47%. However, once we adjust for changes in the purchasing power of the dollar, then using official US government inflation statistics (the CPI-U as calculated by the Bureau of Labor Statistics), a dollar by the end of 2012 would only purchase what 69.9 cents would have purchased 15 years before. So when we take our ending index value of 1426, and we adjust for the change in purchasing power, our ending purchasing power is only 997 (as shown in blue), or a gain of 27.

Out of what appears to be a 47% gain, then, once we adjust for the changing purchasing power of the dollar, only 2.7% of the gain turns out to be real. And the remaining 44.3% was really just illusion in the form of inflation. We basically just maintained our purchasing power and came out a slight bit ahead. (My article "How Financial Reality Is Hidden By Commonly Used Theory And Jargon" discusses this illusion in much further detail.)

Assuming we started with an initial investment of $100,000, if the stocks in our portfolio performed exactly like the stocks comprising the S&P 500, then on a price-only basis our ending portfolio value would have been $146,965. Subtracting the initial investment leaves us with $46,965 in profits, as shown in the dark blue bar on the above graph and line (2) on the chart.

When we take the declining purchasing power of the dollar into account, it turns out that $44,228 of our "profit", is really just keeping up with inflation. (The red bar and line 3.)

After adjusting for inflation, we find that our real profits (pretax) are in fact only $2,737, as shown in the green bar and line 4.

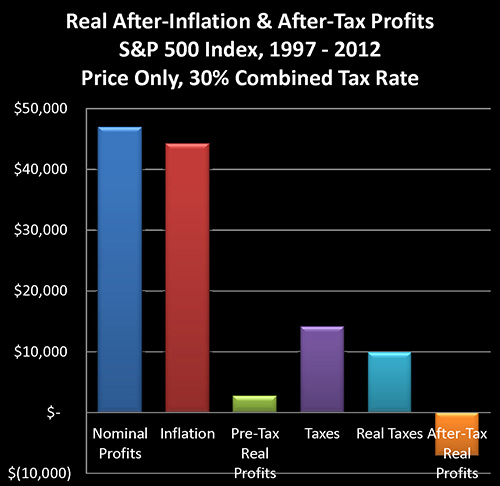

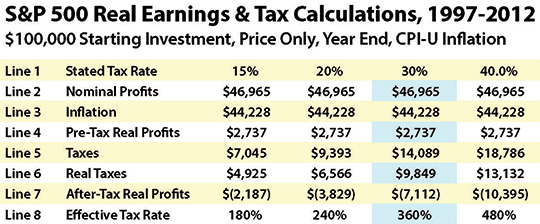

The four right-hand columns in the chart are for varying tax rate assumptions, on a combined state and federal basis. We will be using the assumption of a 30% tax rate for this walk-through.

Now again, even though inflation is caused by the government through a combination of fiscal and monetary policy, the Internal Revenue Service does not recognize inflation as a deduction. Therefore, it treats the entire $46,965 shown in line 2 as being taxable income. When we apply a 30% tax rate (assumed combined federal and state marginal rates) to this, we come up with $14,089 in taxes due, as shown in line 5, as well as the purple bar of the graph.

Adjust the taxes for inflation, and our real taxes are $9,849, as shown in line 6, and the aqua bar of the graph.

When we subtract our inflation-adjusted taxes (line 6) from our inflation-adjusted income (line 4), we find that the real after-inflation and after-tax bottom line is a loss of $7,112. On a reality basis, then, we didn't make 47% – but rather we lost 7% of our original investment.

A 100% income tax rate on real (after-inflation) profits would have taken our entire 2.7% in real profits, leaving us at breakeven. With a 7% loss, however, we did worse than break even. Therefore, our real tax rate must actually be higher than 100% of our real income.

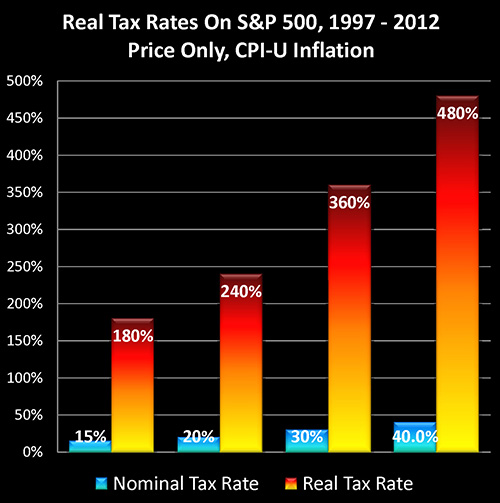

When we divide real taxes (line 6), into real income (line 4), we get the real tax rate on real income. For our 30% tax rate example, then, we divide $9,849 in inflation-adjusted taxes by $2,737 of inflation-adjusted income, and perhaps to our surprise, we find that our real tax rate is 360%, as shown in line 8 of the chart, and also illustrated in the graph above.

As further shown in the chart and graph, for the 15 years analyzed and looking at actual price changes in the Standard & Poor's 500 index, a 15% stated tax rate translated into a real tax rate of 180%, while a 20% stated tax rate translated into a 240% real tax rate, and a 40% marginal (federal and state) stated tax rate became a 480% real tax rate.

Fully taking inflation and stock index price changes into account, the real impact of the increase in the long-term capital gains tax rate in the United States wasn't to go from 15% to 20%, but rather from 180% to 240%.

The real tax rates may look fantastically high when compared to stated tax rates, but the source is easy to see – once we know what to look for. Simply return to our "Real After-Inflation And After-Tax Profits" graph and visually compare the towering size of the red "Inflation" bar, to the thin little sliver of the green "Pre-Tax Real Profits" bar.

It's not just that impressive looking price gains were almost entirely based on the destruction of the value of the dollar hiding miniscule real returns, but worse – that illusion of income is fully taxable. The red bar in the graph above is every bit as taxable as the green bar. And once income taxes are paid on the towering phantom income of inflation, the result is that all of our real income was taken by the government, and a great deal more besides.

Transforming After-Tax Assets To Pre-Tax Income

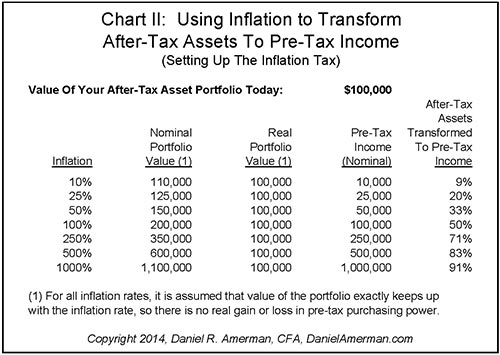

There is a very important principle that long-term investors of all kinds are wise to remember: the higher the inflation rate – the greater the percentage of your assets that belongs to the government. This applies not just to taxes on ongoing income, but after-tax assets as well.

In the initial round number tutorial, we looked at what happened with a 100% rate of inflation. The nominal value of our asset doubled – and we moved from having 100% of our $100,000 asset being after-tax, to having $100,000 in pre-tax income (50% of our asset), and $100,000 in an after-tax asset (50% of our asset). The government just transformed 50% of our assets from after-tax to pre-tax.

Income that it is then entitled to tax us upon whenever we trigger a tax effect, say by moving our investment to a different form, or trying to spend part of it. Income that doesn’t economically exist in purchasing power terms, but was artificially generated through the government's destroying the value of the currency.

What the chart below demonstrates is the government’s powerful incentive to increase the inflation rate, if it wants to maximize tax dollars. As shown, the higher the rate of inflation – the more of your assets becomes pre-tax income that is subject to taxation.

With the example $100,000 portfolio, a 10% rate of inflation raises the nominal value of our portfolio to $110,000, meaning we have incurred $10,000 in pre-tax income – even though the real value of our investments haven’t budged. This means that 9% of our real $100,000 in after-tax assets just became taxable income. The percentage of assets transformed steadily increases with the rate of inflation, until we reach the bottom row where we see that inflation of 1000% will have the effect of transforming 91% of our assets from after-tax to pre-tax, as we are now subject to taxation on a full $1 million in illusory income.

Compounding The Problem – Repeated Raids

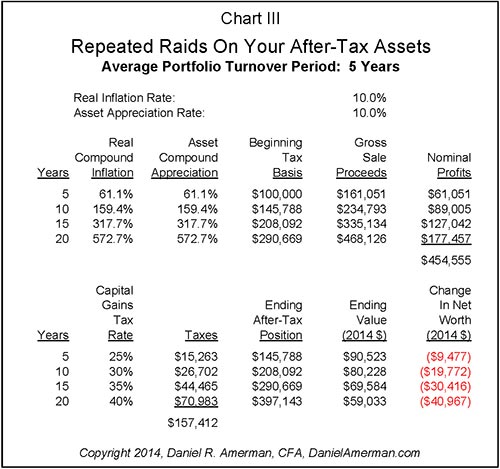

There is a particularly unfortunate aspect to the inflation tax – which is that it isn’t a one-time tax. For instance, let’s say we own an asset for five years, inflation turns 50% of our asset from after-tax assets to pre-tax income, we sell the asset, pay the taxes, buy another asset – and then we start over again. Because ongoing future inflation will again create another level of pre-tax income, that will be taxed again. This principle is illustrated in the chart below:

To show how the chart works, let’s say you start out with $100,000, inflation averages an annual 10% over the next 20 years, and through excellent asset choices you are able to do what most investors are not and earn 10% annually, so that you keep up with inflation. On a pre-tax basis, anyway. You try your best to follow a long-term investment strategy that minimizes tax consequences, but the world is in financial turmoil, and you do need to turn your portfolio over into new investments an average of once every five years.

For the first five year period, inflation and matching investment success on your part have raised the value of your portfolio to $161,000 (rounded). The economic value is still $100,000, but inflation has created $61,000 in nominal income, meaning 38% ($61,000/$161,000) of your portfolio has been converted from after-tax assets to pre-tax income. You pay a little over $15,000 in capital gains taxes at a rate of 25% (tax rates are assumed to rise by 5% every five years as the Boomers increasingly reach retirement age and everyone pays more), and you are left with $146,000 in after-tax assets. When adjusted for inflation, you have about $90,000 of your original $100,000 in purchasing power remaining, and this means the inflation tax has claimed about 10% of your assets.

Then it starts again, as 38% of your after-tax assets are converted to pre-tax income, you pay a little higher tax rate, and lose about another 10% of your after-tax real net worth. Repeat, and repeat again – and after 4 rounds and 20 years, you have ending assets of $397,000, but they are only worth $59,000 in purchasing power, and you have lost 41% of the real value of your starting $100,000 in assets to repeated rounds of the Inflation Tax. Keep in mind as well that these assumptions are relatively benign in some ways, for a five year turnover is very slow by many standards, and for simplicity and conservatism we’ve kept all your income qualifying for capital gains tax treatment. The bite of the inflation tax is much worse when applied on an annual basis and at short term tax rates.

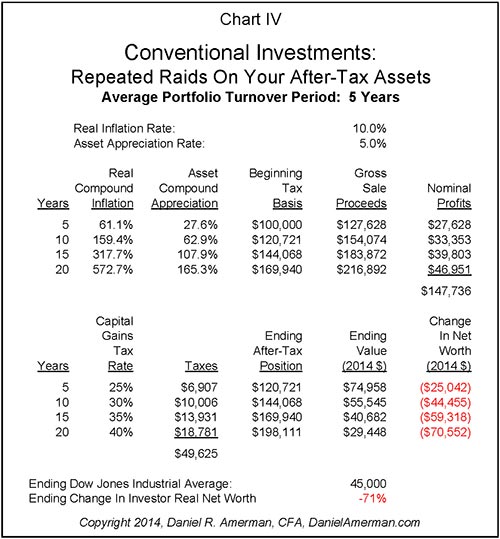

Conventional Investments May Fare Much Worse

The worst pain from the inflation tax may be reserved for conventional investors. We'll illustrate with the chart below, and making a few simple assumptions. Let’s assume that the stock market rises by 5% a year, and that a $100,000 investment has increased to $128,000 in the next five years (call it the DJIA reaching 21,500). That 28% profit looks great at first glance! Except the problem is that average annual real inflation levels rose at a 10% annual rate instead of a 5% annual rate, for total compounded inflation of 61%. So the real value of the Dow in purchasing power terms has in fact dropped substantially, even while the nominal value soared. The stock investor has fared significantly worse than a tangible asset investor who has succeeded in staying even in pre-tax, real dollar terms.

Now, let’s assume that the original $100,000 in assets had been purchased with after-tax dollars, so the government had no right to the assets. However, the government does have rights to the $27,000 increase in the nominal value of the assets, even though the real value was falling in purchasing power terms. Again assuming that capital gains tax rates rise as Boomer retirement finance problems soar upwards, the investor would pay $7,000 in taxes. That leaves $121,000 – but the $121,000 is only worth $75,000 thousand in 2014 dollars. So the combination of government fiscal policy destroying the value of the dollar, and government tax policy taxing non-existent profits created by the destruction of the dollar, have taken 25% of the investor’s portfolio.

Then it happens again, and again, and again. Until at the end of 20 years, the Dow now stands at 45,000 (with triumphant newspaper headlines every step of the way) – and the investor has lost 71% of the value of their assets on an inflation-adjusted and tax-adjusted basis.

A Reliable & Politically Advantageous Way Of Taking Wealth

This could be a good time to ask yourself three questions:

1. Do you believe that the US government has tens of trillions of dollars of unfunded retirement obligations?

2. Do you think that politicians have a preference for raising money via hidden taxes on private wealth that the general public does not understand, instead of openly seizing retirement accounts or sending stated tax rates through the roof?

3. Might many of your friends and neighbors have been paying these kinds of taxes for years without realizing what is happening?

(Even if they are investing inside a tax-deferred account like an IRA or 401 plan, the hidden taxes will still be paid in full as the account is drawn down.)

If you answered "yes", and we put all three of those factors together, then we can see the overwhelming need, the powerful motivation and the absolutely proven and politically reliable method.

These hidden taxes are an important part of our past and present, and whether people know they exist or not does affect their being real (indeed, they work better when the victims have no idea and therefore no defense).

Because of the overwhelming financial issues associated with heavily indebted and aging nations who have made very expensive retirement promises – there is an excellent chance that these hidden taxes may play a much larger role in all of our financial futures.

What you have just read is an "eye-opener" about one aspect of the often hidden redistributions of wealth that go on all around us, every day.

What you have just read is an "eye-opener" about one aspect of the often hidden redistributions of wealth that go on all around us, every day.

A personal retirement "eye-opener" linked here shows how the government's actions to reduce interest payments on the national debt can reduce retirement investment wealth accumulation by 95% over thirty years, and how the government is reducing standards of living for those already retired by almost 50%.

A personal retirement "eye-opener" linked here shows how the government's actions to reduce interest payments on the national debt can reduce retirement investment wealth accumulation by 95% over thirty years, and how the government is reducing standards of living for those already retired by almost 50%.

An "eye-opener" tutorial of a quite different kind is linked here, and it shows how governments use inflation and the tax code to take wealth from unknowing precious metals investors, so that the higher inflation goes, and the higher precious metals prices climb - the more of the investor's net worth ends up with the government.

An "eye-opener" tutorial of a quite different kind is linked here, and it shows how governments use inflation and the tax code to take wealth from unknowing precious metals investors, so that the higher inflation goes, and the higher precious metals prices climb - the more of the investor's net worth ends up with the government.

Another "eye-opener" tutorial is linked here, and it shows how governments can use the 1-2 combination of their control over both interest rates and inflation to take wealth from unsuspecting private savers in order to pay down massive public debts.

Another "eye-opener" tutorial is linked here, and it shows how governments can use the 1-2 combination of their control over both interest rates and inflation to take wealth from unsuspecting private savers in order to pay down massive public debts.

If you find these "eye-openers" to be interesting and useful, there is an entire free book of them available here, including many that are only in the book. The advantage to the book is that the tutorials can build on each other, so that in combination we can find ways of defending ourselves, and even learn how to position ourselves to benefit from the hidden redistributions of wealth.